• Parish close of Dirinon

• Parish close of La Martyre

• Parish close of Landerneau – Saint-Thomas

• Parish close of La Roche Maurice

• Parish close of Le Tréhou

• Parish close of Loc-Eguiner-Saint-Thégonnec

• Parish close of Pencran

• Parish close of Pleyben

• Parish close of Pleyber-Christ

• Parish close of Ploudiry

• Parish close of Plougonven

• Parish close of Plounéour-Ménez

• Parish close of Plourin-lès-Morlaix

• Parish close of Saint-Jean-du-Doigt

• Parish close of Saint-Thégonnec

• Parish close of Tréflévénez

• Parish close of Trémaouezan

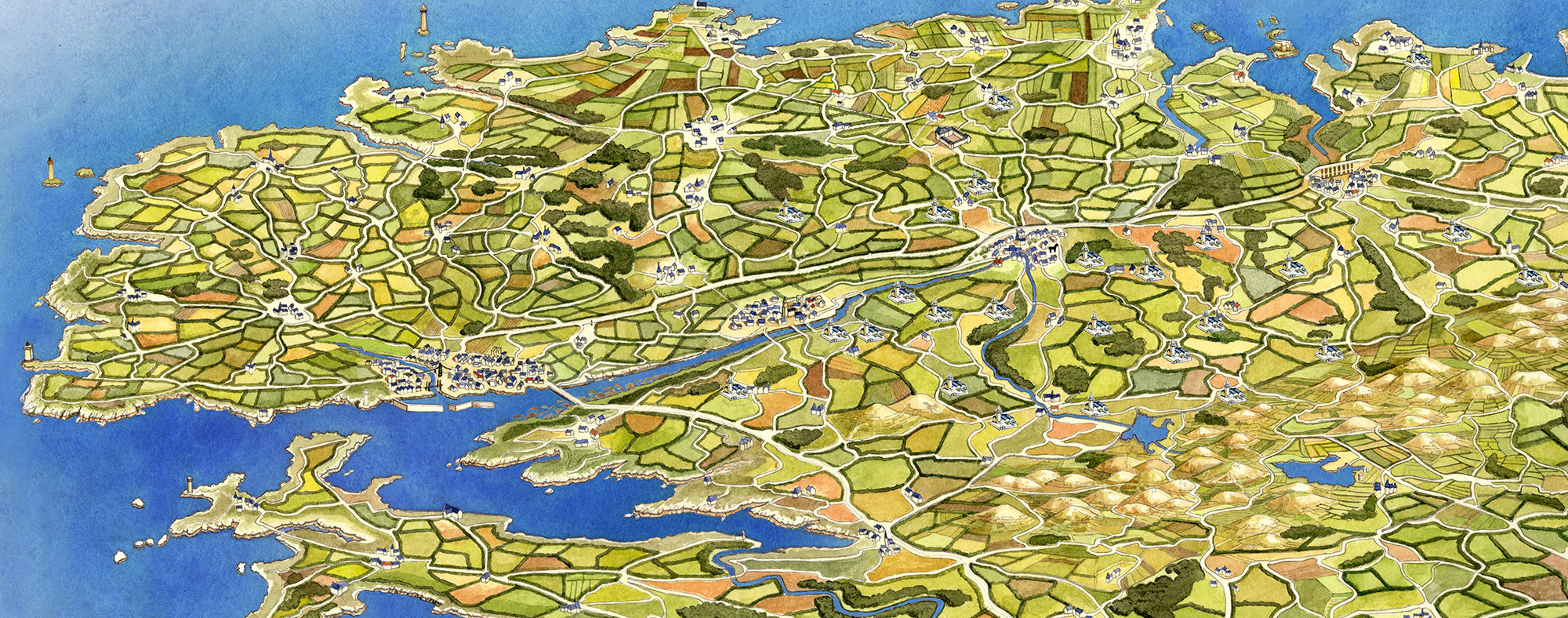

Land of the parish closes

Discover the land of the parish closes

Parish close of Dirinon

In the very masculine world of Celtic saints, the Welsh Saint Non is rather an exception. Her cult is widespread across the Channel, but in Brittany, Dirinon is almost the only example. The chapel adjoining the church (1577) does in fact preserve a mid 15th century recumbent effigy, with a beautiful face, full of serenity. It is mistakenly taken for the saint’s tomb but the parish does have her relics in a silver reliquary from the same period (about 1450). Outside the village Saint Non also has a very beautiful holy spring (1623) and not far from that, a stone which is the object of an enduring cult.

Saint Non has also inspired a ‘mystery play’ of nearly 3000 lines in Breton which was probably written and performed here at the end of the 16th century : the Buez santes Nonn hac ez map Deuy (Life of Saint Non and her son Divy). Non was a novice at an abbey in Wales when she was raped by a prince named Kérétic. She therefore took herself off to Dirinon, where, in an oak forest, she gave birth to a son, Saint Divy (David). The text, which is of exceptional linguistic and historical interest is kept today in the National Library in Paris.

It was in this same period that the parish close was built, as a result of the prosperity of the cloth trade and the patronage of noble families who have left their coats-of-arms, in a niche of the calvary (15th century), for example. If Dirinon belongs to the diocese of Quimper, certainly its characteristics attach it to Léon, starting with the double-galleried bell-tower (1588) which challenges La Roche-Maurice for the origin of this style. The church was built immediately after, with its porch flanked by a small attached ossuary (1618) with rectangular windows. At the beginning of the 18th century it was enlarged by a choir and a transept higher than the nave. This was no doubt when the wood-panelled vaulted ceiling received the painted decoration which is unique in this area : saints, evangelists and learned men leading the gaze towards the Last Judgment.

Parish close of La Martyre

Forebear of the great bell-towers (14th century, on even older foundation), oldest of the triumphal gates (about 1450), an exceptionally early porch (middle of the 15th century), painted murals in the nave… the parish close at La Martyre takes us right back to the medieval origins of the “great closes”.

Why such precocity ? Perhaps because we are in a “place of memory” : that of the martyrdom of King Salomon of Brittany (874) whose relics the church preserves. But above all because this was the site of an influential international fair right up to the 17th century. Each July the village attracted merchants from all over the west of France, but also from Flanders and England, perhaps even further afield. After all, the great stained-glass window of the choir was inspired by a work of the German engraver Iost de Necker, whose signature the glass-worker faithfully reproduced.

From the 14th century, the revenues of the fair and the joint patronage of the Dukes of Brittany and the Rohan family authorized ambitious achievements : the bell-tower was inspired by the spires of the cathedral of St-Pol-de-Léon. The porch, which the passage of time and the surviving coloured pigment makes especially moving, is rich in details of great finesse : the smile of the reclining Virgin on the tympanum, as well as the angel announcing the birth of Christ to the shepherds, with one wielding his crook.

However the interior of the porch guards a surprise in the stoup, where Ankou (the Grim Reaper) armed with a spear carries off the head of a young man. The subject comes from the neighbouring ossuary (1619) and it illustrates the lesson written in Breton on the sombre, beautiful Renaissance façade : “Death, Judgement and cold Hell, man must tremble when he looks on these”. After the smile of the Middle Ages, the anxieties of the 17th century…but it must not be forgotten that the interior of the church completes the message : the colours (stained-glass windows and altarpieces) and gilding aim to evoke in anticipatory fashion the splendours of the Hereafter.

Parish close of Landerneau Saint-Thomas

Situated on a crossroads of routes leading to Quimper, essential point of passage between the dioceses of Léon and Cornouaille, the parish close of St Thomas has lost its original appearance since the 19th century, and we have no surviving picture of it.

Of the original close only the church and the ossuary remain. It was dismantled in the 19th century, especially at the time when the cemetery was moved outside the town. A boundary wall must once have marked the sacred space surrounding the cemetery, and like all the closes, a calvary would have been the dominant feature. Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury and canonized in 1173 after his martyrdom, was patron of the church, chosen by its founder, Hervé 1st, lord of Léon, thus marking his desire to assert his independence regarding the English ambitions of dominance over the Duchy of Brittany.

An earlier church is mentioned in the 13th century, but the one we can see today was reconstructed from the 16th century onwards with a Renaissance bell-tower started in 1607 and rebuilt in the same form in 1847. It consists of a nave of five bays with side-aisles, a chapel and a sacristy south of the last bay occupied by the choir with flat chevet. In the porch is a single statue, that of saint Francis of Assisi in the habit of a Cordelier monk, with the coat-of-arms of a merchant at the base of his tunic, bearing an initial, doubtless that of the said merchant, a generous donor. The ossuary of Saint-Cadou, built correctly to the west of the church, is the second element of this ensemble. Dated to 1635 it began to be used as a habitation in the 19th century.

Parish close of La Roche-Maurice

At the foot of the chateau which belonged to the viscounts of Léon, then the Rohan family, the parish close of La Roche-Maurice occupies an unusual location below the village. Beyond the church, the steep descent continues towards the river (the Elorn) where stones from the Rade de Brest arrived, yellow stone of Logonna-Daoulas and kersanton – which in sunshine contrast sharply on the gable end of the ossuary.

On several occasions, the parish close at La Roche-Maurice made choices that decisively influenced religious art in the region. It was here in about 1589-1590 that the bell-tower of a type called ‘Leonard’ (i.e. from the Léon area) was invented : this has a slender spire resting on a bell-chamber of two levels and two galleries. La Roche-Maurice invented the Gothic version (a spire) exactly at the time when Berven conceived the Renaissance version (a dome). Each style had its followers in many churches of the region over three centuries. The same focus on innovation appeared half a century later with the ossuary of 1639-1640 : plain Corinthian columns replaced the caryatids in fashion since Kerjean, Bodilis or Sizun. Rather than variety and fantasy, La Roche preferred an impeccable purity of lines, classical before its time… but also well in keeping with the severity of its message “I kill you all”, proclaimed by the figure of Ankou on the stoup to the various characters portrayed on the lower level.

There is no great porch here, doubtless because of the constraints of the site. The Renaissance therefore only makes an appearance on the doorway of kersanton giving access to the church, but it breaks out more freely inside : richly detailed string-beams (ploughing, a funeral procession, wrestlers, musicians…), a magnificent painted roodscreen from the 1580s, a stained-glass window of the Passion with the coat-of-arms of the Rohan family, a work probably attributable to workshops in Quimper (1539). In the choir, St Yves dispenses justice, flanked by litigants. It is hardly surprising that such rich ornamentation was not replaced by altarpieces in the following century.

Parish close of Le Tréhou

“An Trevou-Leon” one says in Breton, to distinguish it from Trévoux in Cornouaille. Perhaps also to confirm the Leonard appearance of this borderland parish close, which touches Cornouaille on the south and west sides. And for those who are still doubtful, the tradition affirms that Saint Pitère, patron of this place, was the sister of Saint Suliau (Sizun), Saint Thiviziau (Landivisiau) and Saint Miliau (Guimiliau).

And yet one indication really links the parish close of Tréhou closely with its neighbours in Cornouaille : the abundant use of the yellow stone of Logonna, a quartz microdiorite with veiny appearance which is extracted from the promontory of Roz in Logonna-Daoulas. Its use, frequently associated with kersanton from the Rade de Brest, characterises the region between Landerneau and Daoulas. The calvary of Tréhou (1578) is a good example of this : although very close to that of Locmélar in appearance, it also has Mary Magdalene and the Twelve Apostles carved in relief on its base.

Logonna stone is found in the elegant domed bell-tower (1649), and also in the porch where it alternates with the local beige-coloured granite and the dark grey of the statues in kersanton. In the niche of the tympanum, Saint Pitère sports the palm of martyrdom : her father slit her throat when she refused to marry the husband he had chosen for her. In the interior of the porch several statues bear the initials of their donors : among them a Christ and four apostles by Roland Doré, including Saint Matthew, curiously holding the set-square usually attributed to Saint Thomas. At the base of the vaulted ceiling a string-beam dated 1610 features the instruments of the Passion.

The interior of the church contains a stained-glass window of the Passion, two altarpieces of the 17th century and several ancient statues. On one of the string-beams a workman pushes a powerful wheeled cart. Behind him another peasant is sowing seeds… Outside on the corner of the sacristy a nobleman draws his sword ; a more original figure than the usual dragons in this sort of position.

Parish close of Loc-Eguiner Saint-Thégonnec

Originally many of our parish closes were simple chapels which served various villages (as hamlets distinct from the bourg were called in Brittany). During the Middle Ages or in the 16-17th centuries, some of these became parishes in conditions about which we often have little information. This is not the case with Loc-Eguiner Saint-Thégonnec, the most recent of these promotions. Up to the middle of the 19th century there was just a chapel here, dependent on Plounéour-Ménez : a place (loc = locus) dedicated to Saint Eguiner, whose sacred spring is situated further down. Beside it, another spring, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, may be a sign of the presence of the Knights of the Order of St John.

The parochial bourg was quite a distance – seven long kilometres – especially in winter. For that reason the inhabitants of the surrounding area preferred to patronise this chapel, the oldest parts of which date back to the 16th century. In the course of time it became more independent : on the eve of the Revolution it was managed by two lay treasurers (those of 1736 have left their names on the gable end of the north nave). A chaplain resided on the spot, said mass and ran a little school. Burials were performed here, because there was a cemetery, but it was not the case for baptisms and marriages : only tenacious action by the inhabitants succeeded in obtaining these rights through the status of a parish (1844) and then a commune (1866).

With its simple little bell-tower, the church keeps the appearance of a chapel, but of a good size because it has two adjoining, very neatly constructed, naves. The 16th century calvary was enriched in the following century with a statue of Christ by Roland Doré. But the most venerable stone is the Roman military borne visible to the north of the church. Originally on the Carhaix/Aber-Wrac’h route which passed near the village, it had been topped by an old cross and was transferred into the close in 1948.

Parish close of Pencran

In a region which had largely succumbed first to the seductions of the Renaissance then the Baroque, Pencran offers a Gothic church still resembling the chapel which the inhabitants wanted to build in 1553 “in honour of God, the Virgin and saint Apolline”, as we can read in the porch. It has a simple volume, a nave and side-aisles without adjoining chapels ; a flat chevet like those devised at the end of the Middle Ages, pierced by a great flamboyant stained-glass window ; in the interior there are no altarpieces but Gothic furnishings of which the centrepiece is The Descent from the Cross, a magnificent group sculpture from 1517.

The subsequent centuries respected this Gothic atmosphere overall, perhaps because scruples prevented changes. The great achievement is the south porch, entirely in kersanton, remarkable in both conception and decoration. The group of the Nativity on the tympanum may be mutilated, but the archivolts are brimming with foliage, angels and scenes from the Old and New Testaments. Inside, traces of colour are evident. A height of Breton Gothic… but in the middle of the 16th century, the inhabitants of Pencran were aware of the new taste of the Renaissance, and saved it for the first of the Apostles : have a look inside at the canopy above Saint Peter !

So the Renaissance is present, but it blossoms fully outside the church in the ossuary of 1594 which states plainly what it is in Roman letters and the Breton language : chapel da sant Itrop ha karnel da lakat eskern an pobl (the chapel of saint Eutrope and charnel house for the bones of the people). The parish close also has two calvaries : on the north side, three shafts rise above the monumental entry. It was perhaps here in 1521 that the idea grew up of the double crossing on the central shaft, which gave room for many more characters : it would soon be a model for the whole region. The south side also has its calvary, with the same figure of Mary Magdalene.

Parish close of Pleyben

Although far from the “grand closes” of Léon, Pleyben offers the same mixture of wealth and parish pride. The wealth here derives not from the cloth trade but from fairs, which were created in 1548, with the authorization of Henry II, just before the beginning of the construction of the parish close. A sense of pride comes from the two adjoining bell-towers : the first was a very successful spire (c1550) in Gothic style, but so quickly out of date that the next generation did not hesitate to replicate this element with an enormous Renaissance bell-tower and porch (1588-1642), soon after imitated at St Thégonnec. So the Gothic church, with the openwork gable ends of its chevet, was surrounded by sumptuous additions, like the domed sacristy in green gres (1719), inspired by a prestigious model of the French Renaissance, the chapel of the chateau of Villers-Cotterêts.

The calvary is also on a monumental scale. Originally (in 1555) it was situated near the church and resembled the one at Plougonven, work of the same craftsmen, Bastien and Henry Prigent. The construction of the tower made it necessary to move the calvary in about 1650. On this occasion, an ‘architect’ from Brest, Julien Ozanne, added several scenes to it (including an original Repentance of Saint Peter, on his knees in front of a curious rock with a cock on top). In 1738 the parishioners considerably modified the spirit of the monument in making it a triumphal arch at the entry of the close. This gospel in stone, raised in height, is rather sacrificed from the perspective of the main square, which became a huge open space in the 19th century.

In the same period the tombs moved from the church to the parish close, which in 1725 received a gate called in tell-tale fashion “Porz ar Maro” (The Gate of Death). The Gothic ossuary was transformed into a chapel (the date of 1733 is on the façade). As to the church, it parades the pomp of an organ-case and altarpieces of great beauty, not forgetting beams carved by an unknown hand, but of exceptional quality of inspiration and craftsmanship.

Parish close of Pleyber-Christ

Pleyber-Christ well illustrates the evolution of a parish close from the 16th century to the present day, as a large busy village developed around it. The close lost its graves and the calvary, which were transferred to a new cemetery at the end of the 19th century, before giving up a large part of its land to the neighbouring market-square. A new wall, built from 1905-1906 closely encircles the church : the monument to the dead (1921) took on the aspect of a monumental entry, a role it now actually serves. As to the ossuary, beautifully simple in form, it has survived despite a restrictive location : in its own way it expresses fidelity to the original close.

The church itself has accompanied the growth of Pleyber-Christ from the time of the ‘Golden Age’ of the 16-17th centuries. The parish was boosted by its proximity to Morlaix, port of export for the cloth industry, but also by the dynamism of local paper mills. From 1551 (when the tower was built), the church continued to increase in size up to the beginning of the 18th century : this was a necessary response to the growth of the population and the initiative of noble families who increased the number of seigniorial chapels on both sides of the nave.

In the porch, the beautiful series of twelve Apostles (1667) was the last achievement of the workshop of Roland Doré. Above the door, Saint Peter receives from Christ the task of leading the flock : ‘feed my lambs, feed my sheep’. The chevet, from workshops in the Trégor, presents an original decoration of carved capitals, topped by a statue of the Virgin. The interior is rich in altarpieces (notably a fine Saint Anne teaching Mary) and recently restored string-beams. But the pride of Pleyber-Christ is “ar groaz aour”, a gilded silver processional cross (1620) which can be admired on special occasions.

Parish close of Ploudiry

The ensemble at Ploudiry is most striking for its dimensions : a huge parish close, three monumental entries, a large church and a spacious ossuary. It must be said that it was a very sprawling parish and originally encompassed the territories of La Roche-Maurice, Pencran, La Martyre, Pont-Christ and Loc-Eguiner-Ploudiry. Even today its bell-tower serves as a landmark for the whole surrounding plateau and can be seen from very far away.

More than other buildings, the ossuary’s function was easily surmised when it was built : to shelter bones from graves in the church, which it was necessary to empty from time to time. The niches (then without windows) allowed the bones, which were sprinkled by the faithful with holy water, to be seen. ‘Good people who pass by here, pray to God for the departed’ invites the angel on the stoup to the left. On the upper level, a peasant, a woman, a judge and a noble are shown as equals before Death, which is personified with the traits of Ankou, a skeleton armed with a spear. At Ploudiry as elsewhere, Death was very present in the way of thinking as it was in the everyday life of the population : even at the height of the Golden Age in Brittany there were fierce plagues, notably in the 1630s.

Even though the calvary of the parish close is modest, the porch of the church (1665) ambitiously expands on the Renaissance model started at Lanhouarneau (1582) and Saint-Houarden at Landerneau (1604). Although without upper detail, it is imposing by virtue of its sculpture and the originality of the interior decoration. There one can note two sphinxes, a theme popularised by the Egyptian doorway of the chateau of Fontainebleau (1545). As for the church, largely reconstructed in 1856-1857, its neutral architecture highlights the two altarpieces in the transepts, the work of Jean Berthouloux, who in the 1650s was the first great specialist of the region in this genre. And opposite a remarkable pulpit, an angel supports the head of Christ in a most delicate Pieta.

Parish close of Plougonven

Built in 1554, the calvary of Plougonven was the first large example put up in the Morlaix region. The node of the central cross bears the signature of Bastien and Henry Prigent, the sculptors who shortly afterwards produced the oldest parts of the calvary of Pleyben. From the Annunciation to the Resurrection, the 19 scenes read anti-clockwise starting from the south side – that of the square – which the calvary faces since the restoration of Yan Larhantec (1897). In the place of honour, saint Yves gives justice in favour of a poor man despite the objections of his rich opponent : this is in homage to the church’s patron, who is also the great saint of the Trégor.

Often people are unaware that originally the great calvaries of our region were decked out in bright colours, just like the porches and the façades of some ossuaries. The dark kersanton took on hues of ochre and blue, emphasised by some gilding. All this disappeared over the course of centuries because of the effects of time and atmospheric elements. A new taste eventually decided that our calvaries were never more attractive than in the moving authenticity of natural stone. Some sheltered corners and some documents in the archives preserve the memory of those colours… enough to keep alive the dream of renewing this forgotten aesthetic.

Not far from here at Plourin-lès-Morlaix, eight statues by the sculptor Roland Doré regained their colours in 1994 : six of them can be seen in the niches of the ossuary. At Plougonven the painter Marco di Napoli encourages us to use our imagination in accessing the original colours of the calvary, certain traces of which were still visible at the end of the 19th century. The knowledge of ancient pigments, freely interpreted, helps to re-establish the calvary in the visual universe of the Bretons of the time : put in colour, the Evangelist in stone is firmly the comrade of the figure portrayed at same moment in the stained-glass windows or religious mystery plays.

Parish close of Plounéour-Ménez

As its name indicates Plounéour-Ménez belongs to “the mountain” (menez in Breton), which is to say the Monts d’Arrée, the highest point of which (Roc’h Ruz, 385m) is in the commune. Here as elsewhere, the parish close owes much to the cloth industry : the height of linen production can be divined behind this large church, reconstructed in 1649-1651 to receive the living and the dead of a very extensive parish. But the pleasant opulence appropriate for a cloth-producing area takes on a more severe appearance in the harsh approaches of the mountain. Here power prevails over opulence.

The power is perhaps first of all inherent in the stone. Not kersanton : the granite of Plounéour-Ménez, well used throughout the region, here enjoys almost a complete monopoly. The proximity of deposits made sizeable superb stones of grand appearance easily available not just for the church, but also for an entire stretch of the surrounding wall. Power is also shown in the monumental gate (17th century) of two arches, inspired by Saint-Thégonnec and without embellishment. It is in the simplicity of the porch, flanked by a little stair-tower giving access to the archive room, as one can see in the Trégor area. It is also in the great mountain slates which cover the three adjoining naves. And it is of course in the rough, strong silhouette of the large bell-tower (1665) which shares with its twin (and elder) Commana the audacious gamble of foregoing a gallery and small bell-towers.

The close has lost its ossuary (destroyed in the 19th century), but it has two calvaries, with the most remarkable situated outside at the foot of the tower. Here, exceptionally, Plounéour-Ménez succumbed to the charms of kersanton and the talent of Roland Doré, creator of the statues on the upper cross-piece. On the lower level, St Yves makes the gesture of a judge, counting out legal arguments on his fingers : he shares the patronage of the parish with the unknown saint Enéour.

Parish close of Plourin-lès-Morlaix

To explore the territory of the parish closes is to encounter Roland Doré, one of the rare sculptors whose name has come down to us, all over the place. This is the case because he signed several works (Saint-Thégonnec, Commana), and because his name appears in various archives, but especially because his work is recognisable at a glance : straight and clear lines, clothes with stiff folds and perhaps above all, those lean faces with almond-shaped eyes. Up until his death in 1663, Doré’s workshop at Landerneau produced hundreds of pieces, worked in kersanton and distributed over Léon, Trégor and Cornouaille : major pieces of work like the porch at Guimiliau, series of Apostles for other porches (Trémaouézan, Pleyber-Christ…), and nearly 80 crosses or calvaries placed close to churches and chapels, or just in simple crossroads locations.

On the edge of parish close country in Trégor, Plourin-lès-Morlaix had recourse to the talent of Roland Doré. Six statues by the master of Landerneau today occupy the niches of the ossuary, exceptionally still decorated in a range of colours which help us to imagine the hues of the original. The four Evangelists, each with their symbolic attribute, accompany two Doctors of the Church, Gregory and Augustine (or Ambrose). Seven other statues, including the set-piece Flight into Egypt, are spread between the wall of the close and the church. These are the remains of a rather important calvary constructed here about 1630 by Doré, which was taken down at an unknown date.

As to the church of Notre-Dame, it illustrates the ideal of regularity which was established at the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries. There is no longer a south porch, an unnecessary extension at the time when the important people debated matters in the sacristy, but a large bell-tower (1728) remains, inspired by the tower of Saint-Thégonnec, and the interior of the church contains no less than eleven altarpieces occupying the choir, transept and side-chapels.

Parish close of Saint-Jean-du-Doigt

What counted at Saint-Jean-du-Doigt was not cloth, but the crowds of pilgrims who flocked here, in the valley of Traon-Mériadec, to venerate the relic of the finger of Saint John the Baptist which came here about 1400 in unknown circumstances. The parish close didn’t have graves at that time, so the crowds attending the pardon could listen to the preacher who addressed them from a platform (which has disappeared) on the monumental gate. They could be present at mass given in the outdoor oratory and lastly they could carry out their devotions at the magnificent fountain linked to a miraculous spring more than 300m away.

Long before Duchess Anne, responsible for so much according to tradition, such was the magnanimity of pilgrims, the clergy and local nobles well placed close to the dukes, that it enabled the construction, from the 1400s, of something that was not then more than a chapel out of proportion to the surrounding village. The merit for it goes to workshops in Morlaix which carried out almost all the building, from the Gothic tower – so elegant with its openwork galleries and little ossuary – to the chevet, also including the porch. In 1576-1577, the outdoor oratory demonstrated a different taste, that of the Renaissance, but it is still the work of a craftsman from Morlaix, the architect Michel Le Borgne. And it was yet another inhabitant of 16th century Morlaix, the goldsmith Guillaume Floc’h, who produced the jewel of the treasure of Saint John : the great chalice with Renaissance ornamentation.

Paradoxically for a site marked by the symbolism of fire, two fires (1925 and 1955) account for the disappearance of the spire and the rich altarpieces, but fortunately they spared the collection of gold and silver cult objects. Taken back to the dizzying purity of its original volumes, the building happily welcomes contemporary creativity : since 1990 the ensemble of stained-glass windows (80 square metres) have been brought back to life and meaning, thanks to the work of Louis-René Petit.

Parish close of Saint-Thégonnec

In the ‘family’ of parish closes, Saint-Thégonnec can be seen as the crowning glory. And a spectacular one at that, as it reflects the prosperity of a parish that was the richest in Léon at the zenith of the cloth industry, about 1670-1680. The two bell-towers, the triumphal gate and all the interior decoration (restored after a fire in 1998) positively ooze with pride of the whole community, even if the names one can read here and there showcase the richest in particular : Jean Mazé and Jeanne Inizan, who in 1625 ordered the beautiful Saint John of the porch from Roland Doré, are an example of the merchant-manufacturers who controlled the fabrication and distribution of cloth around Morlaix.

Crowning glory indeed. The calvary (1610), centred on a most expressive Passion, is one of the last great ensembles in the Léon region. The ossuary (1676-1681) could pass for an aesthetic achievement simply by virtue of its balance and symmetry : more than at Lampaul-Guimiliau, it invites reflection on death, to the rhythm of the inscriptions which encircle the walls (there are no bones here : they were placed in a more modest monument no longer in existence). As to the church, it also goes further, or rather higher ; at the beginning of the 18th century, when the decline of the cloth industry in Léon made it generally impossible to envisage any more large-scale works, the continued prosperity of Saint-Thégonnec allowed the height of the nave to be raised and allow in more light.

Behind all these stages of construction which continued through six generations – one or two more than elsewhere – we can perceive a tenacious concern to follow the evolution of trends as closely as possible : from 1599 this impulse resulted in doubling the first bell-tower – a Gothic spire still recent but already outdated – with a magisterial Renaissance tower, which, like at Pleyben, took the place of the porch. An exceptional richness, a pride without reservations, a repeated attraction towards innovation : it is all this that makes Saint-Thégonnec ‘different’.

Parish close of Tréflévenez

In the wealthy procession of parish closes in Léon, Tréflévénez has good reason to feel a little ill at ease. Starting from the entrance, a simple calvary of 1871 ; an ossuary with a handsome façade in yellow Logonna stone (1611) has barely been preserved ; a composite façade which is adorned with a bell-tower more in the style of Cornouaille than Léon with its short spire without a gallery constructed on a very openwork bell-chamber ; on the south flank, a porch which has never passed the stage of intention…

And yet this church offers many riches which one seeks in vain elsewhere. In the south aisle, an aristocratic tomb struck with the coat-of-arms of the Huon de Kérézellec family speaks in Latin of a father’s love for his dead son. On the neighbouring wall an astonishing painting of the Crucifixion (1696) was discovered during the removal of the altar of the Rosary : there is the trace of an earlier altarpiece, in trompe-l’oeil, which allowed a breathing-space until the finances of the parish council allowed a real one to be put in place. Not far from there, different wooden panels represent the ‘good death’ or recall the liberation of a man imprisoned by the Turks and ransomed by the intercession of a monk (1721). Near the fonts, Saint Margaret emerges from an astonishing dragon. On the string-beam in the nave, one can spot two motifs dear to carpenters of the 16th century : Reynard the fox preaching to chickens and a pig playing the biniou (bag-pipe) … but a man with a rosary is not far away.

The church is equally distinguished by the delicacy of its colours : the whitewash of the masonry and blue-grey of the panelled ceiling, dotted with angels, set off the livelier tones of the hoops of the vaults and the colours of the stained-glass window in the chevet (a Passion from the years 1560-1570). The church has preserved two panelled altarpieces from the 18th century, on each side of the north aisle. In the choir, the little blue and gold altarpiece recalls those of Sizun and Le Tréhou and is doubtless from the workshops of Landerneau.

Parish close of Trémaouézan

‘An Dre’, as they say in Breton : a religious dependency (trève), which indicates more than a chapel but less than a parish : such was the statute of Trémaouézan before the Revolution. Still today the village preserves its intimacy, far from the main routes. And yet it was here, at the beginning of the 17th century that a monumental porch was constructed, strictly comparable with the greatest of the region, Saint-Houardon of Landerneau or Guimiliau. And it is here too that the vanguard of Baroque altarpieces arrived from the 1640s, a style which would become widespread in the following decades.

Indeed, there was a time at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries when Trémaouézan saw a spectacular rise in its fortunes. Originally the cult united the Virgin Mary (Intron Varia an Dre) and Saint John the Baptist : each patron of a sacred spring (the second, from 1656, is still visible at 200m from the church). In a context of fervour, exacerbated by the menace of epidemics, Trémaouézan saw a great increase in processions and pilgrimages from all sides. The little Gothic close, which we can still get an idea of from the calvary and ossuary, was encouraged to think big…

Neither money nor ambition was lacking. From 1597 the church was almost doubled in size by the addition of a vast perpendicular chapel, a little on the lines of the great sanctuary of neighbouring Le Folgoët. From 1610 a large Renaissance porch was constructed on the south side of the church, despite the risk of disproportion. Several indications show that excellence was the goal : the use of kersanton, the fluted and banded columns devised by Philibert de l’Orme, statues produced by the workshop of Roland Doré (Virgin and Apostles), the weighty Latin inscription on the grandiose pediment… With a deliberate originality, the upper floor of the archive room opens onto a balustrade which could – like the great calvaries of the same era – serve as a place of preaching during large gatherings.